What can metaphors tell us about personality?

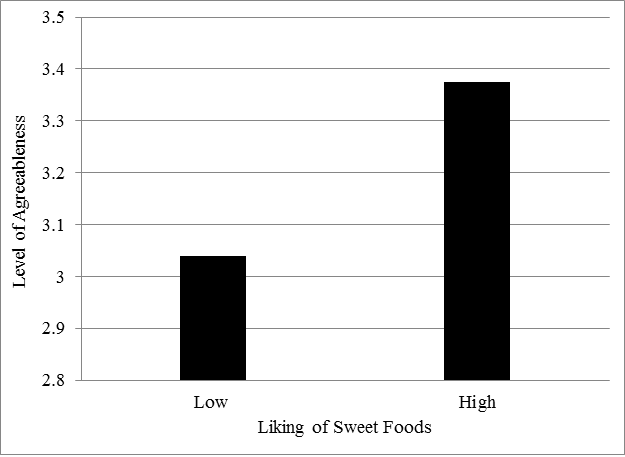

In another preference-related investigation, Meier et al. (2012) focused on metaphors linking agreeable personalities to sweet tastes. A first study established that people claiming to like sweet foods (relative to other tastes) were judged to be more agreeable. The second study was particularly interesting. In this study, people were asked how much they liked foods that were sweet (e.g., ice cream), bitter (e.g., celery), salty (e.g., pretzels), sour (e.g., cottage cheese), and spicy (e.g., salsa). People who liked sweet foods, in particular, scored higher on the trait of agreeableness. A representative result of this type is displayed in Figure 2. A third study found that people who liked sweet foods to a greater extent were more helpful in their behavior, for example by volunteering for a city-wide flood cleanup effort in Fargo, North Dakota. When in need, then, you might be better off turning to your friend that always orders dessert rather than your friend that never does.

W Figure 2. Levels of Agreeableness as a Function of Liking Sweet Foods (Low versus High).hy do preference-related judgments work in capturing differences between people, though? We suggest that people are drawn toward experiences (e.g., colors or tastes) that metaphorically fit their personalities (Robinson & Fetterman, in press; Swann, 1992). Accordingly, hostile people like red precisely because: (a) they are hostile and (b) hostility is metaphorically red. Similarly, agreeable people like sweet tastes because: (a) they are agreeable and (b) agreeableness is metaphorically sweet. If so, preference-related judgments can be recommended in future studies of metaphor and personality as well. For example, we should expect (and we have found) that depressed people prefer “dark” to “light”, consistent with prominent metaphors for depression (e.g., “being in a dark place”).

Figure 2. Levels of Agreeableness as a Function of Liking Sweet Foods (Low versus High).hy do preference-related judgments work in capturing differences between people, though? We suggest that people are drawn toward experiences (e.g., colors or tastes) that metaphorically fit their personalities (Robinson & Fetterman, in press; Swann, 1992). Accordingly, hostile people like red precisely because: (a) they are hostile and (b) hostility is metaphorically red. Similarly, agreeable people like sweet tastes because: (a) they are agreeable and (b) agreeableness is metaphorically sweet. If so, preference-related judgments can be recommended in future studies of metaphor and personality as well. For example, we should expect (and we have found) that depressed people prefer “dark” to “light”, consistent with prominent metaphors for depression (e.g., “being in a dark place”).

The self’s metaphoric location

Most people feel as if the “self” resides somewhere in the body. However, the body has many different parts. Which of these do we associate with the self? From Plato onward, two particular body parts and their metaphoric functions have been highlighted (Swan, 2009). Somewhat simplistically stated, the heart is emotional and the head is logical. There are many metaphoric phrases of this type. To “follow one’s heart” is to follow one’s emotional sentiments, whereas to “have one’s head on straight” is to approach interactions in a rational, if not logical, manner. A person “has a big heart” to the extent that his/her positive feelings for others are pronounced, is “in one’s head” to the extent that he/she is somewhat detached, and many phrases metaphorically pit these two body parts against each other (e.g., “my heart says yes, but my head says no”).

Given the prominence of such metaphors, it seemed potentially useful to ask people whether they conceptualize themselves more as heart- or head-related entities. A simple forced choice question of this type was created. Subsequently, answers to this question were found to be important to the individual difference literature (Fetterman & Robinson, in press). Across studies, approximately 50% of people chose the heart as the locus of the self and 50% chose the head. Emotionality is higher among females (Robinson & Clore, 2002) and, consistent with this point, more females than males thought the self was located in the heart.

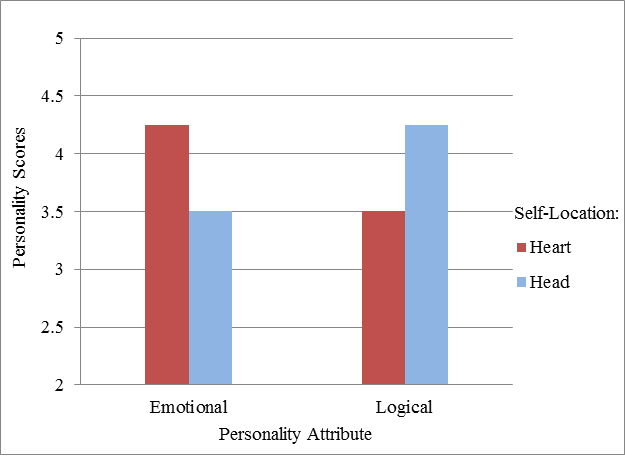

Figure 3. Idealized Emotional and Logical Personality Scores for Heart versus Head Locators.Of perhaps more importance were the personality-related findings. Heart-locators scored higher on measures of emotionality and interpersonal warmth. Head-locators described themselves as more logical, but they also scored higher in interpersonal coldness and were less agreeable. These results are quite consistent with metaphors for the heart (e.g., it is emotional) versus the head (e.g., it is logical). It was also found that heart-locators preferred relying on intuition, whereas head-locators preferred relying on rational thought, when making decisions. Other studies established that head-locators had higher GPAs and answered general knowledge questions more accurately and that heart-locators were more likely to solve moral dilemmas in an emotional manner. Figure 3 presents idealized data of the type found in the Fetterman and Robinson (in press) paper.

Figure 3. Idealized Emotional and Logical Personality Scores for Heart versus Head Locators.Of perhaps more importance were the personality-related findings. Heart-locators scored higher on measures of emotionality and interpersonal warmth. Head-locators described themselves as more logical, but they also scored higher in interpersonal coldness and were less agreeable. These results are quite consistent with metaphors for the heart (e.g., it is emotional) versus the head (e.g., it is logical). It was also found that heart-locators preferred relying on intuition, whereas head-locators preferred relying on rational thought, when making decisions. Other studies established that head-locators had higher GPAs and answered general knowledge questions more accurately and that heart-locators were more likely to solve moral dilemmas in an emotional manner. Figure 3 presents idealized data of the type found in the Fetterman and Robinson (in press) paper.

One further study extended this analysis to daily patterns of emotion and behavior. Consistent with the idea that heart-locators are more emotional, they (relative to head-locators) reacted to stressful events with more intense negative emotions. Consistent with the idea that head-locators are more interpersonally hostile, they (relative to heart-locators) reacted to daily provocations with greater aggressive behavior (e.g., arguing and yelling). Additional analyses indicated that the head-heart measure was unique in its ability to account for the diversity of findings obtained across studies (Fetterman & Robinson, in press).