To affinity and beyond! How our preference to be among similar people interacts with our social ecology

Obviously, educational attainment has a big impact on occupational status and income. What this means is that now more than ever, couples are either very well-off (both earning a high income) or not at all (both earning low incomes). The uncomfortable result of this is that socioeconomic inequality among households for our generation is much higher than it was when households had spouses of mixed educational levels. In fact, economists have shown that rising income inequality in the US can be explained by people marrying people with similar levels of educational attainment (Greenwood, Guner, Kocharkov, & Santos, 2014). If anything, it appears that if it weren’t for people marrying people with similar levels of education, economic inequality is the United States would be falling instead of rising!

Preferences for similarity and residential segregation

The same preference for similarity can also have implications for segregation and fragmentation of the neighborhoods in which we live. Social scientists have been studying segregation of neighborhoods, based on factors such as ethnicity, race, and income for decades (e.g., Massey & Denton, 1988). How did cities in the US get so segregated? In the case of ethnic and racial segregation, one common explanation is ‘white flight’ or tipping (Grodzins, 1957). When “undesired” minorities move into a predominantly white neighborhood, the theory is that whites tend to pack up and leave.

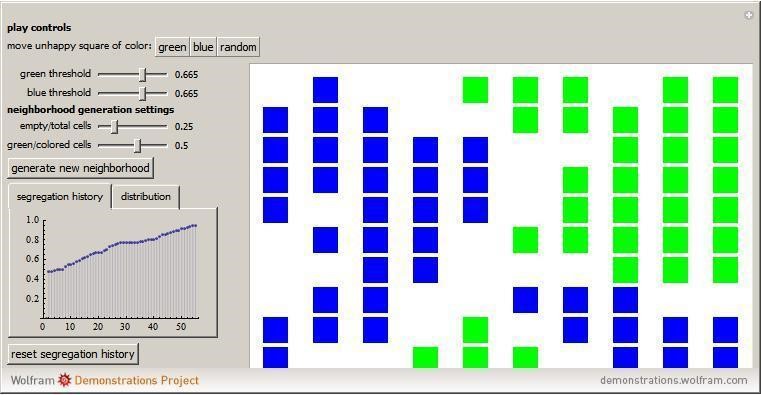

But what if our seemingly benign preference for similar others is once again the culprit here? Economist and Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling (1971) demonstrated through a simple agent-based simulation model that this indeed may be the case. Schelling created a grid-like structure where the cells represented housing opportunities, and agents of different types would occupy these cells with the opportunity to relocate. The ‘free-will’ of these simulated agents worked along a threshold mechanic. At each step of the simulation, the agent would take a look at the other agents who “lived” in the adjacent cells. If enough of these agents were of a different type, the agent would more to a new neighborhood, or in other words, they would relocate to a random empty cell that was surrounded by more similar agents.

Schelling found that when agents preferred cells that were surrounded by at least one-half of similar agents, striking patterns of segregation would occur. In fact, eventually the system would achieve close to the mathematically maximum amount of segregation possible given the parameters. Schelling also found that uneven populations would enhance the segregation. When one population outnumbered the other 3:1 or 4:1, the minority population would very quickly form a large homogenous cluster. This was because the low initial numbers of cells containing similar others caused the minority to relocate aggressively in the early stages of the simulation.

More recently, researchers have tried to update Schelling’s original model to accommodate the more complex nature of real neighborhoods. The fashionable thing to do now is use continuous preference functions, where the probability of moving isn’t black or white, but comes in shades of grey. Bruch and Mare (2006; 2009) argue that these functions generate less segregation compared to Schelling’s threshold functions. However, Van de Rijt, Siegel, and Macy (2009), found a disconcerting result: when simulated agents were sensitive to how the composition of their neighborhoods were changing in terms of the number of agents similar to themselves, the simulation could become very segregated once again, even with built-in parameters for diversity and tolerance.

Race isn’t the only factor by which neighborhoods can become segregated based on people’s decisions to relocate to live near similar others. For instance, some investigations have proposed that residential mobility may be increasing the political polarization of the United States, as individuals tend to move to places which match their political ideologies. In his book The Big Sort, Bill Bishop (2009) argues that ideologically-based migration is leading to a more polarized society. More recently, Motyl and colleagues (2014) showed that people whose ideologies did not fit with community were more likely to want to relocate to a new neighborhood. The same thing appears to happen with wealth, as wealthy couples tend to relocate to expensive metropolitan areas, inadvertently leading to rural areas becoming poorer (Costa & Kahn, 1999). These investigations suggest that greater residential mobility, combined housing choice (choices in where one relocates to), can translate into higher levels of homogeneity within neighborhoods in wide number of domains.

Fig 1. The progression of residential segregation over time, in the Schelling model of residential segregation. You can try experimenting with a demonstration of Schelling’s simulation yourself. (Requires Wolfram cdf player plugin)

http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/SchellingsModelOfResidentialSegregation/