Manipulating the body, measuring the body, and tinkering in the name of Psychology

In these three studies, participants had no real reason to move their bodies, but they did, and this movement was tracked by the researchers. In another type of experiments, participants get an instruction to move in a specific way, and it is studied how quickly and accurately they can do that. The trick is here that the correct movements are made easy or hard by other ideas that again come from embodied representations.

Here is an example experiment following this strategy (Zwaan & Taylor, 2006): Participants were presented with complete sentences and asked to judge whether these made sense (some did not). In order to indicate their judgment, participants had to turn a rotating knob either to the left in one condition or to the right in another condition. Some sentences implied movement, for instance “He turned down the volume”, typically a counter-clockwise movement on many devices. By now you will probably guess what happened: Judging the correctness of this sentence was easier (and thus faster) when having to perform a counter-clockwise movement to do so, and the opposite occured for sentences implying clockwise movements. (This type of experiment has a long tradition, going back to the 90s, when Solarz (1960) built a system with mechanical levers participants had to push and pull.)

These were all examples involving movements, but measuring the body does not end there. Psychologists have studied various physiological processes for a long time: changes in heartbeat, breathing, sweating, hormonal changes, and movements of facial muscles, such as smiling and frowning (see Blascovich, 2014, for an overview). For instance, it is known that the temperature of the body and fingers change in certain patterns when emotions are experienced (Ekman, Levenson, & Friesen, 1983). Similarly, IJzerman and colleagues (2012) have recently found that when a person is excluded socially from a group, their finger temperature drops somewhat. They used a very precise industrial thermometer hooked up to a computer to measure finger temperature. Following an embodiment reasoning, the idea is that such physiological processes feed back into our feeling and thinking.

How to measure the body, or tinkering in the name of Psychology

It is noteworthy that all these efforts involve technology of some kind. Some of the examples use general recording technology combined with a lot of laborious coding. Other experiments creatively adapt consumer hardware such as joysticks, WII balance boards or keyboards for their purposes, often adding special computer programs. Still others use expensive and specialized technology, such as expensive professional motion trackers.

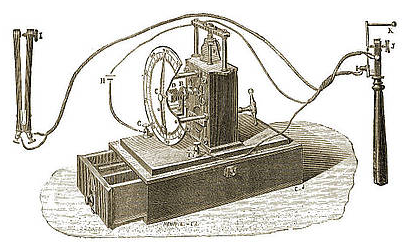

There is a long tradition of psychologists tinkering with technology to measure behaviour. It actually goes back all the way to the founding fathers of modern psychology, such as Galton, Wundt, Helmholtz, and others, who all built wondrous devices to measure behaviour, including its speed (see Figure 1). Obviously, technology and tinkering with it is needed to come up with ways to fuel a new wave of embodiment research that measures the living body. What can that be?

Clock designed by Jacques-Arsène d'Arsonval (1851-1940) to measure speed of transmission in nerves.

Clock designed by Jacques-Arsène d'Arsonval (1851-1940) to measure speed of transmission in nerves.

It just so happens that this need for measurement technology coincides with a renaissance of tinkerers and makers in general. The availability of open source software and hardware that is cheap and flexible has led to an increase of people who dare to build hardware themselves, and program it themselves. In computer science departments and elsewhere, so-called maker spaces are opening, inviting people to experiment with building their own gadgets.

One cornerstone of this movement is a family of small microcontroller boards called Arduino – essentially tiny computers that have only the fraction of the power of a PC, but also cost only the fraction of a PC (see a TED video at [http://on.ted.com/Arduino], and find out more at their website [http://arduino.cc/]). These microcontroller boards can be hooked up to a PC, and become themselves the hub for a range of sensors. For instance, you can get sensors that measure acceleration, position in space, temperature, or distance to the nearest object, typically for just a few euros. It is easily conceivable that all kinds of measurement instruments for embodiment studies can be built with this hardware, measuring movements and positions of body parts, or skin temperature, to name just a few.

Of course, this will not reach the precision of professional hardware. However, what may be more important than excellent precision is that a community has sprung up around these Arduino boards and hardware in general, where know-how and computer code is shared openly. Measuring the body becomes affordable and workable.