Your mother, metaphors, and other monkey business: How experiences of physical warmth shape how we think about relationships

Now what does this have to do with the metaphor story? Psychologist Mark Landau and his colleagues (2010) recently proposed that we can analyze people’s conceptual thoughts by examining the properties of two different schemas in order to understand much more complex concepts, through a process called metaphoric transfer strategy. Through this strategy, we can come to understand how people combine different schemas through so-called conceptual metaphors (see Lakoff & Johnson, 1999). Conceptual metaphors combine the physical experiences of one concept with the more abstract properties of another concept. For instance, the expression “Friday is far away” may seem natural, but actually reflects the use of a spatial description (distance) for a temporal property (the time until Friday). Thus, in order to understand some very complex ideas about time, we recruit the more intuitive concept of space (see Boroditsky & Ramscar, 2002, and Casasanto & Boroditsky, 2008, for more information on this idea).

Your mother, metaphor, and other matters

But why might people build up such associations? In building the case for conceptual metaphors, Lakoff and Johnson (1999) discuss the idea of primary metaphors. Because people may jointly express concepts like time and space in metaphors (e.g., like the earlier mentioned Friday being far away), they may acquire a very basic association between related concepts that one acquires early and often. Furthermore, such associations come to exist between abstract concepts (such as social phenomena) and more concrete experience (such as physiological states).

Let us now return to the subject of interpersonal warmth. Time and space are not the only concepts you experience jointly; the world is rich with examples of metaphoric transfer. The primary focus of our research has been on the relationship between physical warmth and feelings of affection. From the moment of your birth, you have experienced feelings of affection and physical warmth jointly – most likely beginning when your mother used to hold you. This is a very basic body-mind connection that has been recognized by many social psychologists.

Because social connections are so fundamentally important to people, social psychologists have proposed that interpersonal warmth is the most important dimension on how we judge people (Asch, 1946; Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2007). It is thus only natural that interpersonal warmth has been the focus of research investigating metaphoric structuring. A couple of years ago, Lawrence Williams and John Bargh (2008) wanted to test the link between physical and psychological warmth. In keeping with the hypothesized link between psychological and physiological warmth, people that had just held a cup of warm coffee (versus a cup of iced coffee) judged a third person as more sociable and more affectionate – entirely indicative of a warm personality! In a follow-up study, Williams and Bargh even found that people became more generous after having a warm gel pack placed on their neck. And indeed, these effects reflect something about how we learn relationships: Young children show similar effects, but only if they are securely attached (IJzerman, Karremans, Thomsen, & Schubert, in press). These ideas have been elaborated on since – but may go beyond conceptual metaphors.

Our Thoughts: Just Monkey Business?

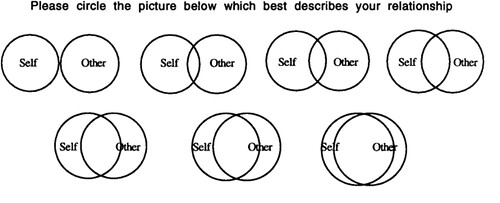

In recent years, we have conducted a number of studies to test how physical warmth may influence people’s psyche. Our findings indicate that in addition to affecting judgements of others and generosity, physical warmth is associated with a broader array of effects. When we put our participants in a warm room, they judged the experimenter they had just interacted with as being psychologically closer. We tested this through a pictorial scale, in which one circle represents the participant and the other the experimenter – through an oft-used measurement in research on relationships (see e.g., Aron, Aron, & Smollan, 1991; Gunz, 2008; and the illustration below).

In addition to this, we even found that a warm room also lead to participants using more verbs (as compared to adjectives; Peter kisses Gwen, for example, illustrates their relationships, whereas Peter is a loving partner does not) and adopting a relational perceptual focus (seeing the relationship between objects, rather than the properties; for an example, see the figure below, choice A). The findings from these studies provide strong support that physiological states are linked to social concepts.