Seeing and Believing: Common Courtroom Myths in Eyewitness Memory

Even though Susan was mistaken in her identification, she is an example of a seemingly-credible witness. She provided an accurate description of the perpetrator, reported valuable information, including the assailant’s claim that he had a white girlfriend, and identified his silver bicycle. A local with a history of assault that matched the reported characteristics, later confessed to the rape. She was not a “bad” witness, but a well-intentioned and helpful one, who understandably put her trust in the police agents guiding her through the investigation. Unfortunately, she was attempting to identify a man of a different race from a biased lineup (Anderson’s was the only color photo placed among black-and-white mugshots). By the time the trial took place, Susan had been exposed to a multitude of variables known to have adverse effects on eyewitness memory. As a consequence, her ability to make an accurate identification during the investigation and a fair assessment of her stated confidence during the trial in that identification was impaired.

The memory of eyewitnesses is malleable, and their reconstructions are dependent on a complex interplay of personal, situational, and social factors (e.g., the witness’ distance from the perpetrator, individual memory-strength, interviewing techniques). It is crucially important for those involved in criminal cases to engage in understanding such factors that may impact memory and to critically evaluate the evidence presented, rather than blindly accepting or indiscriminately rejecting eyewitnesses.

Myth #2: Everyone Knows When Eyewitnesses Are Unreliable

Many of the high-profile exoneration cases, such as the Anderson case above, emerged from crimes committed and tried in a time when DNA testing was virtually unheard of. Today, cases like Anderson’s have fixed a media spotlight on causes of wrongful convictions and external influences on eyewitness evidence, and we have decades of psychological research on eyewitness memory. Some European countries and a handful of states in the U.S. have adopted identification procedures to align with scientific recommendations.

Yet biased lineups and erroneous identification are still a significant risk. A case in point is that of Henry Osagiede, a Nigerian native who was convicted of robbery and sexual assault in Spain in 2008 (Epifanio v. Madrid, 2009). Both victims, who described the assailant as a black man, identified Osagiede from a live lineup with complete certainty. Based on this evidence, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. The Spanish Supreme Court overturned the conviction a year later when it came to light that the convicted man was identified from a biased identification procedure: Placed among four Latin-Americans, Osagiede was the only black man in the lineup.

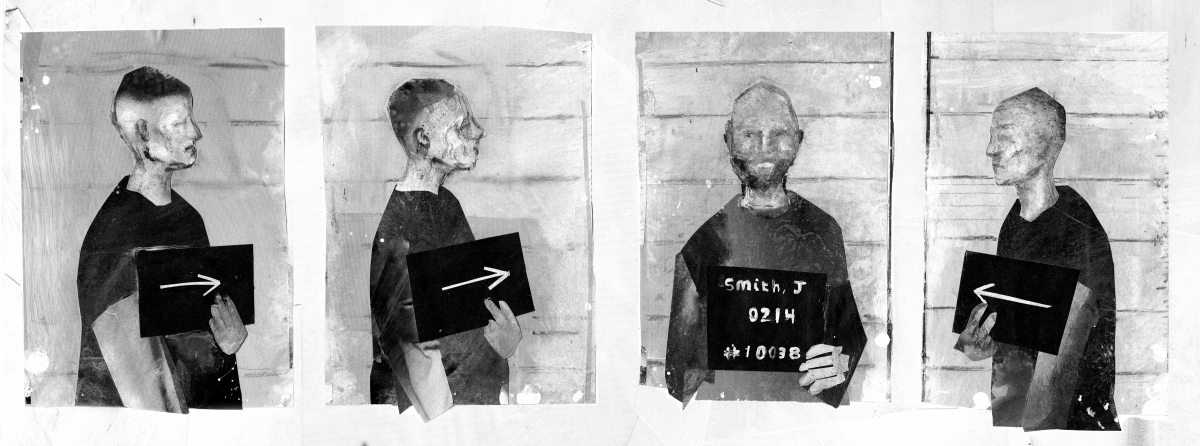

'Police Lineup' by Grace Alexandra Russell (http://www.gracerussell.co.uk/)

'Police Lineup' by Grace Alexandra Russell (http://www.gracerussell.co.uk/)

In the lab, psychologists demonstrate how seemingly-harmless decisions in constructing a lineup can easily bias someone to choose the suspect - whether that suspect is guilty or not. Lineup fairness can be assessed by providing non-witnesses (people who are ignorant to the identity of the perpetrator) with a description of the perpetrator and then asking them to pick out the lineup-member that best matches that description (Doob & Kirshenbaum, 1973). If the lineup is fair, responses should be evenly spread among the lineup members presented. This is what the Eyewitness Identification Research Laboratory at the University of Texas (El Paso) did with the lineup of a perpetrator described as an African-American, male teenager with long, braided hair (n.d.). Although the lineup was constructed with six African-American teens, 95% of non-witnesses managed to pick out the police suspect - the only person with braided hair. In this case, a positive identification only demonstrates that the eyewitness is able to identify the most reasonable option. Unfortunately, juries and judges often only see the final result of a police identification lineup. Without the relevant background information or documentation of the actual lineup, there is no real means of judging the reliability of a positive suspect identification.

In cases like Osagiede, it is clear that influences proven to impact the ability of eyewitnesses to make accurate identifications were not considered. Even more alarming is when such influences are not revealed to or considered by judges and juries making life-altering decisions to convict or acquit the accused. Perhaps “everyone knows” that eyewitnesses can be inaccurate, but it can easily be forgotten, ignored, or lost in translation when applied to investigatory and legal decision-making.

Myth #3: Consistency Is the Hallmark of the Reliable Witness

In the legal arena, consistency is considered a vital means of determining witness credibility. Police officers intuitively distrust accounts that change from one telling to the next (Krix, Sauerland, Lorei, & Rispens, 2015) and lawyers use inconsistencies to discredit a witness on the stand (Fisher, Brewer, & Mitchell, 2009). In fact, juries in the U.S. are instructed to use statement consistency as a critical factor in determining the credibility of an eyewitness. However, inconsistencies appear any time we rely on memory, and are not necessarily evidence of a defective or deceptive witness.