Children are poor witnesses. Or are they?

Importantly, such cases were not exclusively American. In Germany, the Wormser- and the Montessori-trials are notable examples of cases in which children’s statements were likely the result of suggestive interviewing techniques (Schade & Harschneck, 2000). Furthermore, in the Netherlands, the alleged ritual abuse of about 50 children between the ages of three to 11 by strangers in the city Oude Pekela was highly debated (Jonker & Jonker-Bakker, 1997). Notably, all these cases started with a vague initial suspicion that evolved into serious and precise allegations with life-changing consequences for the suspect.

The question can be raised whether children’s vulnerability as eyewitnesses is due to memory impairments or adults creating an atmosphere of speculation and rumour transmission. Important in this branch of research is Principe, in whose studies children watched a magic show where the rabbit-out-of-hat trick failed (Principe & Schindewolf, 2012). The children were then assigned to different groups among which one group overheard an adult conversation about why the trick failed and how the rabbit escaped. This group and another group of their classmates were the rumour groups. After a two-week-delay, their statements were compared to a group that actually witnessed a rabbit running around after the magic show. Intriguingly, no differences were present between these groups on reporting the loose rabbit (Principe, Kanaya, Ceci, & Singh, 2006). Thus, children can remember a witnessed event, but false memories might be due to their vulnerability to elaborate on rumours.

The bottom-line message emerging from the legal cases and the related research was that false memories are more prevalent among children than adults, and hence children’s testimonial accuracy is inferior to that of adults. However, this view has recently been challenged by a series of studies showing age-related increases in false memories. For example, younger children were less likely to infer and elaborate on the loose rabbit rumour when only clues (i.e., nibbled carrot) suggested its escape than older children (Principe, Guiliano, & Root, 2008). These diametrical findings challenge the child’s supposed inability to make credible statements. It even suggests that not children but adults are more susceptible to certain false memories.

The strength of children’s testimony

To understand how such seemingly conflicting patterns can occur, with children being sometimes more and other times less vulnerable to false memories than adults, it is imperative to differentiate between different types of false memories. The formation of false memories can be caused by internal and external factors (Brainerd, Reyna, & Ceci, 2008). Externally-driven false memories are also called suggestion-induced false memories. These are frequently elicited experimentally using a classical misinformation paradigm originally introduced by Loftus, Miller, and Burns (1978).

This paradigm contains three main phases: (1) participants are exposed to an event (e.g., a slide show of a car accident), (2) they are confronted with misinformation (a question suggesting that the car stopped in front of a stop sign even though it was a yield sign), and (3) they have to answer final memory questions concerning the content of the original event. Research has shown that a significant minority of participants incorporate the misinformation into their memory reports and develop false memories. Moreover, children are considered to be more prone to this misinformation effect than adults (Loftus, 2005).

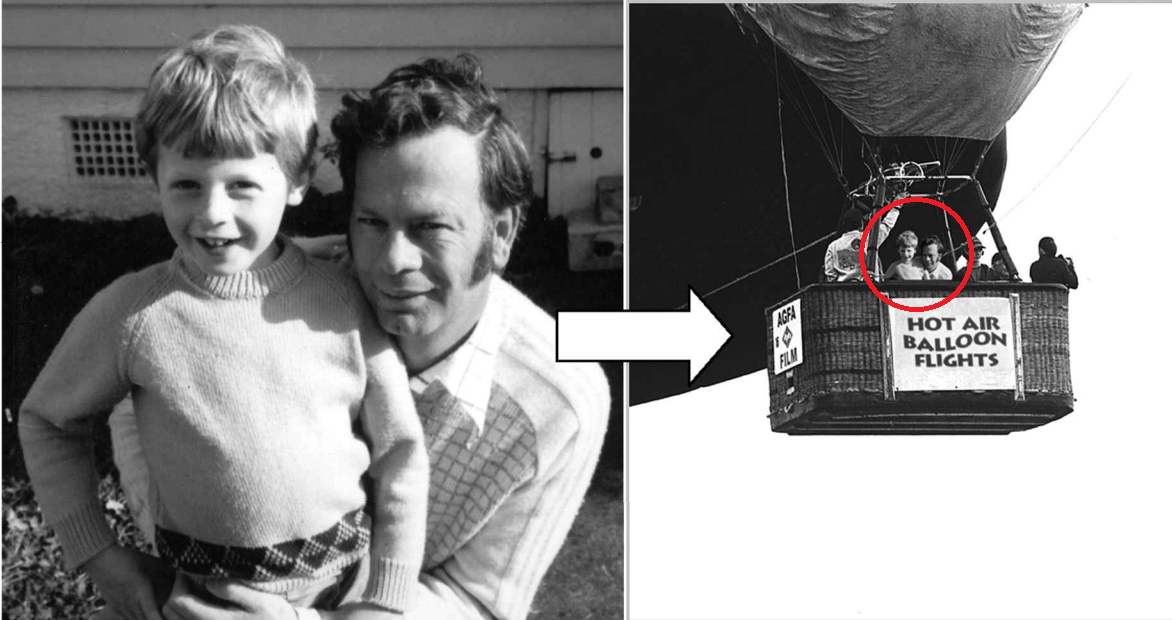

Indeed, researchers have shown that it is possible to implant false memories for entire events. For instance, participants provided vivid and detailed descriptions of a hot air balloon ride they actually never experienced in response to the presentation of a manipulated photograph (see Figure 1; Wade, Garry, Read, & Lindsay, 2002). In children, this misinformation effect can be obtained for highly implausible events, such as an UFO-abduction (Otgaar, Candel, Merckelbach, & Wade, 2009). Again, children were more susceptible to implanted false memories than adults.

Internally-driven false memories, on the other hand, emerge without external influence. They are called spontaneous false memories. A robust method to study this phenomenon is the Deese/Roediger-McDermott (DRM)-paradigm (Deese, 1959; Roediger & McDermott, 1995). In a typical DRM experiment, participants are instructed to study word lists. The words semantically relate to each other (e.g., young, female, dolls, dress, cute, hair) while one critical related word is missing (i.e., girl). In final memory tests, adult participants falsely “remember” this critical word with rates comparable to those of the presented words (Roediger, Watson, McDermott, & Gallo, 2001).